Lesson 1 – Critical and Systems Evaluation of News Articles

Description: In this activity, the students will be introduced to the fascinating world of extremophiles. The students will brainstorm questions and research these unique organisms. In the following lesson, students will be presented with a real-life example of an event that affected the Great Salt Lake ecosystem, the building of a causeway.

Objectives

Course: Life Science, Integrated Science, STEM, BioChem, Marine Science

Unit: Ocean Acidification, Ecology, Biogeochemical Cycling

See the NGSS buttons in the left-hand panel of this page for an overview of the standards addressed in this lesson. Also, please see the documents on the Standards Addressed page for all NGSS, WA State (Science, Math and Literacy), and NOAA Ocean Literacy Education Standards connections. In particular, for this module, due to the variety of experiments completed within classrooms, students will learn and do a variety of activities. Because each student will complete different labs in this module, each student will not complete all of the listed standards. However, ideally, they will complete 1-2 sets of performance expectations. To give you a broad, big-picture overview, in addition to the aligned objectives linked above, for this lesson, here is an overview of:

What Students Learn

- There are many real case studies demonstrating dramatic and subtle changes in the Earth’s carbon cycle.

- Scientific news articles are written for a variety of purposes. Critically assessing what you read is an important skill.

- Concept maps are a useful tool to understand news articles. Nodes are the parts of a network map, and edges are the relationships between those parts of the network.

- Studying a real-world complex problem is possible in the classroom.

- When studying complexity

- collaboration is essential,

- a big picture view is necessary as is the ability to analyze subnetworks within a system.

What Students Do

- Students focus on reading one news piece to critically assess the

- content (what is correct, incorrect, supported by evidence, not supported, etc.)

- authors’ motivation,

- misconceptions and/or preconceived notions.

- Students begin internalizing the practices of systems thinking by recognizing the indirect and direct connections between abiotic and biotic components in our world.

- Students develop and demonstrate the habits of open-minded, metacognitive dialogue.

- Students develop the skills of collaboration.

Instructions

Pacing Guide: One to Two 50-minute period.

When teaching the topics of ocean acidification, climate change, environmental science, and sustainability, helping students learn to critically assess print and electronic articles, such as those found in newspapers, websites, magazines, journals, etc., is of utmost importance. In this lesson, each student in your class will read a different short news piece on various engaging and thought-provoking topics surrounding the changing carbon cycle.

Prerequisites

- This lesson and unit are most effective when students have had some exposure to networks and systems dynamics. The Introduction to Systems module (Lesson 1 & 2) or our Systems are Everywhere module are both effective ways to build systems thinking skills. These lessons can be easily connected to these ocean acidification (OA) lessons in addition to many other life and physical science topics. See the embedded links to connect to these lessons.

- Pre-assess student understanding using this worksheet: PreAssessment OA.doc (Google Doc | Word Doc)

- This can be completed for homework and/or the previous day. Students can complete the hard copy preassessment or the online survey monkey preassessment (https://www.surveymonkey.com/s/XKSWTML). Explain to students that this is not a “test” and they are not expected to know every answer. This is merely a beginning step towards evaluating the lessons and understanding where their thoughts are at this exact moment. Encourage them to write something down for each answer.

Lesson Instructions

We recommend this lesson be completed in-class instead of as a homework assignment. Since the lesson is meant to introduce this sometimes controversial subject, it is important to provide an environment where students are able to read quietly and assess their thoughts in reference to their article.

Step 1: Pass out one article for each student (download PDF of Combined 50 Articles | grab PDF from Google Drive) along with a copy of the Reading Guide (Word | Google Doc). To save paper, you could instead bring your students to the computer lab and have each student access the appropriate link for their article. This can be found in the combined PDF (download PDF of Combined 50 Articles | grab PDF from Google Drive). And they could fill out the question guide electronically. The articles are numbered to account for the number of students you have in your class. The articles have been prioritized to make sure each class set has a broad enough set of articles to complete the next activity. If you would like to add new articles to the 50 we have provided, feel free to do so. However, keep in mind that you want your students to see a large, global, systems-wide effect on many biotic (living) and abiotic (nonliving) components of land, sea and air. You also want them to see that CO2 is a common, testable, key to all of the issues brought up in these articles. Make sure to hand out at least articles numbered 1-10. We have also provided a readability score for each article and a summary, for teacher use only, of most of the articles (Word | Google Doc). At the end of the summary document are other suggested, longer articles.

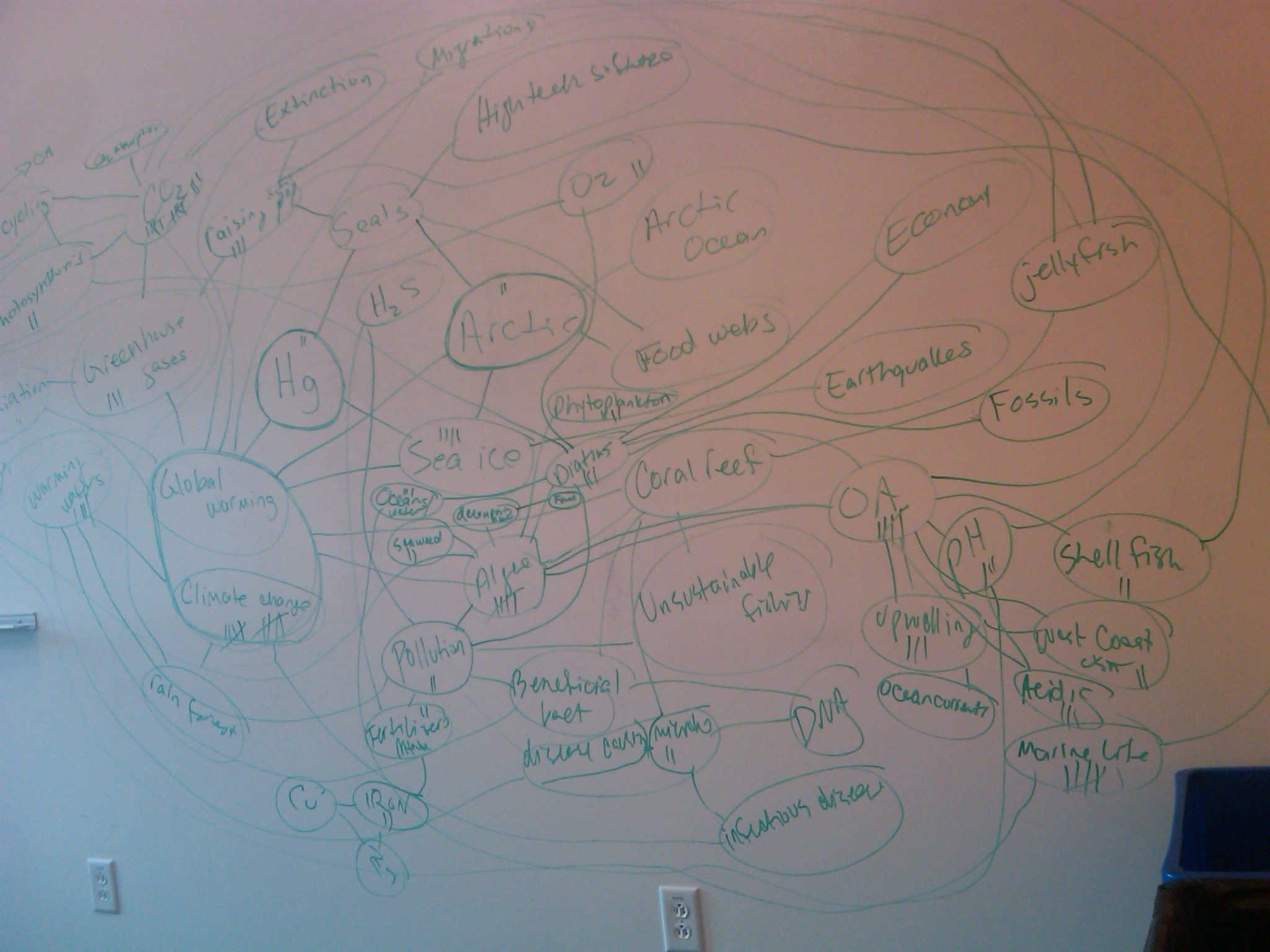

Step 2: This step should guide students toward being able to answer questions such as: What are common threads? What big issues are addressed? If this issue were important to your community as a community member, scientist, policy developer (politician) what tactic might you use to understand this issue and if needed work toward a solution to this problem? Would systems thinking be useful in this endeavor? How can we, in our classroom, study this problem? Instruct the students to have their completed Reading Guide and article on their desk. Moving at a fairly quick pace, have each student, one at a time, give you the keywords from their article. Each time a student mentions a similar keyword, instead of re-writing that keyword, keep track of how many times each word is used. Develop a concept map of all of the keywords as they connect to other words from other articles. Use the concept map as a way of having the students decide as a group what is important and possible to study (CO2). As a homework assignment, ask students to record their ideas for possible experiments in their journal or lab notebook. They should give a summary of the day’s activity and write possible questions they might explore in the lab to learn more about the changing carbon cycle and its effects.  Here’s an example of a concept map that was quickly, collaboratively created after reading a set of 35 articles. The purpose for including the image is not to read every node, but to see how a quickly created diagram can help students see how connected many aspects of the environment are. The CO2 node is in the upper-righthand corner with the highest number of article “mentions.” Also displayed is a cleaned-up example of what students collaboratively created, visualized with Cytoscape.

Here’s an example of a concept map that was quickly, collaboratively created after reading a set of 35 articles. The purpose for including the image is not to read every node, but to see how a quickly created diagram can help students see how connected many aspects of the environment are. The CO2 node is in the upper-righthand corner with the highest number of article “mentions.” Also displayed is a cleaned-up example of what students collaboratively created, visualized with Cytoscape.

Three groups have prepared variations for teaching this lesson.

I. The California State Board of Education has recommended using word clouds as a variation via their publicly available Framework as part of Chapter 7.2. We have slightly adapted their recommendations here:

- Have students submit their keywords to an online form.

- Monitor the results as they are submitted.

- Paste the keywords into a word cloud generator (where the keywords appear in an image with the font size of each word proportional to how often it is used). CO2 is by far the largest word and a number of other words were utilized multiple times.

- Or you can allow your students to add words directly into a word cloud generator. There are many good, free tools for this. One SEE Educators like to use is Slido which has a profanity filter, is easy to share with students, and has an easy way to save completed word clouds. You can find Slido at https://www.sli.do/ or https://www.slido.com.

- While the word cloud is good for identifying the common threads, it fails at showing how these common ideas relate to one another.

- Divide the class up into groups of four and give each group a large sheet of paper. Each group must arrange the submitted keywords from the entire class into a single network or concept map. Students snap photos of their maps and upload them to the class webpage. For homework, they will refer to their map and write a short research proposal with an argument [SEP-7] justifying which key concepts they think are most important to investigate, and they brainstorm about how they could investigate such topics.

- Or use a tool like Loopy or Cytoscape to map out the relationships. To learn more about Loopy – view our Systems are Everywhere module. To learn more about Cytoscape, view the extension in Lesson 2 of Introduction to Systems.

II. Biology teacher, Cathy Nitchman from Washington State, has her students prepare a Tweet about their article. Please see the documents she has prepared to incorporate this aspect into this lesson:

- Student Reading Guide by Cathy Nitchman (Google Doc | Word Doc)

- Student Guide to Summarize using Twitter by Cathy Nitchman (Google Doc | Word Doc)

III. Yelm School District had their students complete quick rounds of “speed dating” to describe what they learned in their articles.

You completed Instructional Activities. Please move to Assessment via the Tab above.

Assessment

How will I know they know?

- Completed Lab Worksheets and/or Notebook:

- Reading Guide: were students able to thoughtfully complete their Reading Guide? (individual assignment)

- Participation in concept map formation: were students able to successfully participate in creating a group concept map? (group assignment)

- Recording thoughts/ideas in their notebook: were students able to come up with ideas of how they can explore some of their questions in the lab? Were they able to see ways in which they can experiment with carbon dioxide to learn more about the changing carbon cycle? (individual assignment)

- PreAssessment: are students able to consider their previous understanding in order to build onto a framework for future learning? (individual quiz)

Resources

- Student Resource: Preassessment (Google Doc | Word Doc)

- Teacher Resource: Preassessment Answer Key (Google Doc | Word Doc)

- Student Resource: Reading Guide (Google Doc | Word Doc)

- Teacher Resource: Summary of Articles (Google Doc | Word Doc) (which includes a list of other possible articles)

- Teacher Resource: Readability Score for all 50 Articles (PDF)

- Student Resource: Compiled List of 50 Articles (PDF)

- Twitter Adaptation: Student Reading Guide (Google Doc | Word Doc), Student Guide to Summarize using Twitter (Google Doc | Word Doc)

Accommodations

The concept of the health of our environment and of networks can very easily be connected to your students’ daily lives. Think of any needed example, specific to their background and location, to link the examples given in this lesson. For example, if you live on the Olympic Peninsula in WA State, it is likely that your students’ families have worked for timber companies and/or shellfish companies. Both of these industries can be connected to the health of the ecosystem. This is similar in farming communities as well as many others.

Also, to save paper and help develop students’ reading skills, have students read their article on a computer. They can use the Internet to search for unfamiliar words and build their research skills.

Extension

Throughout these lessons, we connect to many terrific resources created by the Ocean Acidification and Climate Change community. This Resource Page is one we update frequently to highlight many of the resources we are aware of. In particular, and as related to this lesson, there is a video that is very helpful to visualize how carbon dioxide amounts have changed over time. The video was created by the Global Monitoring Division of NOAA’s Earth System Research Laboratory (ESRL). To download the video, see the ESRL website, or click here. Likewise, this animation is a powerful way to show students both data and historical trends: ESRL’s Trends in Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide. This curriculum has been written to introduce this animation in Lesson 5B. However, some teachers like to introduce this animation earlier in the module. Wherever you choose to introduce it, make sure to walk students through the content. Due to the large amount of information in this 3-minute animation/video, the big picture can be easily lost unless viewed thoughtfully. See Lesson 5B for more information on how to introduce this content. Suggestion from Jean Ingersoll, who teaches Biology and Marine Science at Glacier Peak High School in Snohomish, WA: My students loved this activity so much, that now I often put together a similar activity to introduce a new unit in class. It’s fairly easy to put together a variety of articles for your students to read, map out and discuss – and it very importantly leads to great learning and deepened interest!

References

The references for the news articles are contained within the links and documents above. Also, many teachers and scientists participated in the creation of these lessons and content. Please view the list of credits for this work.